Physicists are people, possibly slightly crazy, and usually incomprehensible when talking shop, who seek out laws of the universe that can explain and predict how the cosmos works. They use this thing called science to accomplish this feat.

Physicists are people, possibly slightly crazy, and usually incomprehensible when talking shop, who seek out laws of the universe that can explain and predict how the cosmos works. They use this thing called science to accomplish this feat.

But there’s another classification of people, occasionally overlapping with the scientific kind, who have their own mechanisms by which they determine laws of the universe. These are called science fiction authors. Their laws may not necessarily rigorously adhere to the scientific method, but they demonstrate a different kind of insight, one born of the school of hard knocks method.

Perhaps the most famous one is Isaac Asimov, whose Three Laws of Robotics have entered mainstream consciousness through a television show or movie or two. Asimov has been considered one of the big three authors of the golden age of science fiction along with Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein. He’s written hundreds of books, some science fiction, some science nonfiction, and some nonfiction about nearly every topic imaginable.

Perhaps the most famous one is Isaac Asimov, whose Three Laws of Robotics have entered mainstream consciousness through a television show or movie or two. Asimov has been considered one of the big three authors of the golden age of science fiction along with Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein. He’s written hundreds of books, some science fiction, some science nonfiction, and some nonfiction about nearly every topic imaginable.

His most famous fiction focuses on galactic empires and AI robots, each of which had their own series. The empire series began with the Foundation trilogy, then expanded from there. The robot series began with I, Robot, which was adapted into a Will Smith film that had absolutely no similarity to the book whatsoever except the title and the existence of robots.

His most famous fiction focuses on galactic empires and AI robots, each of which had their own series. The empire series began with the Foundation trilogy, then expanded from there. The robot series began with I, Robot, which was adapted into a Will Smith film that had absolutely no similarity to the book whatsoever except the title and the existence of robots.

It was in I, Robot where he introduced his Three Laws of Robotics. They guided the behavior of robots to protect humans from them (so no robot uprising) and were hard-coded into the positronic brains of the robots. Within the Asimovian universe, they were defined in the Handbook of Robotics, 56th Edition, 2058 A.D. They were:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

I, Robot was a series of short stories tied together by the framework of a reporter interviewing a robopsychologist, Dr. Susan Calvin, on her various experiences with troubleshooting robots whose behavior had become irregular. Yes, positronic brains were sufficiently advanced to require psychologists.

I, Robot was a series of short stories tied together by the framework of a reporter interviewing a robopsychologist, Dr. Susan Calvin, on her various experiences with troubleshooting robots whose behavior had become irregular. Yes, positronic brains were sufficiently advanced to require psychologists.

[Spoiler alert] At the end of the series of robot books, the main robot character R. Daneel Olivaw and another robot quietly take over the rule of humans, skirting the three laws by deducing a new law that supersedes them all, which they called the Zeroeth Law:

“A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.”

So, maybe robot uprising after all, but in a nice way.

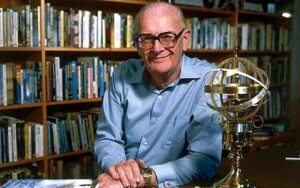

The next most famous series of laws come from Arthur C. Clarke, the second of the great science fiction authors of the golden age and the co-writer of the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey. He didn’t codify them all at once, but devised them over time. They were compiled by others into Clarke’s laws. Clarke chose to stop at three laws because Isaac Newton only had three laws, and he didn’t want to get cocky.

The next most famous series of laws come from Arthur C. Clarke, the second of the great science fiction authors of the golden age and the co-writer of the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey. He didn’t codify them all at once, but devised them over time. They were compiled by others into Clarke’s laws. Clarke chose to stop at three laws because Isaac Newton only had three laws, and he didn’t want to get cocky.

1. When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

1. When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

2. The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.

3. Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

I personally agree with all three of them. The third one is the most famous one. Evidence of that is how many times it’s been paraphrased and satirized with other laws:

• Any sufficiently advanced extraterrestrial intelligence is indistinguishable from God.

• Any sufficiently advanced act of benevolence is indistinguishable from malevolence.

• Any sufficiently advanced cluelessness [or incompetence] is indistinguishable from malice.

• Any sufficiently advanced troll is indistinguishable from a genuine kook.

• Any extreme crank is indistinguishable from sufficiently advanced satire.

• Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from a rigged demo.

• Any sufficiently crappy research is indistinguishable from fraud.

• Any technology distinguishable from magic is insufficiently advanced.

• Any technology, no matter how primitive, is magic to those who don’t understand it.

I’m inclined to add an extra law in honor of Clarke:

I’m inclined to add an extra law in honor of Clarke:

• Any sufficiently genius filmmaker can create a groundbreaking science fiction film with the assistance of Arthur C. Clarke.

Larry Niven is another prominent science fiction author with a list of laws. I almost put “Larry Niven was” because I figured he must be deceased by now. But his voice called from his Wikipedia page, “I’m not dead yet.” He’s still going at 83. He was quite prolific with laws and describes them as “how the universe works.”

Larry Niven is another prominent science fiction author with a list of laws. I almost put “Larry Niven was” because I figured he must be deceased by now. But his voice called from his Wikipedia page, “I’m not dead yet.” He’s still going at 83. He was quite prolific with laws and describes them as “how the universe works.”

One law attributed to him turns Clarke’s third law on its head: “Any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology.” Dr. Who borrowed this in an episode where his sidekick Ace quotes Clarke’s third law, and Dr. Who retorts with Niven’s version.

His time travel law requires some analysis: “If the universe…permits the possibility of time travel and of changing the past, then no time machine will be invented in that universe.” Robotics professor and futurist Hans Moravec does the analysis for us:

His time travel law requires some analysis: “If the universe…permits the possibility of time travel and of changing the past, then no time machine will be invented in that universe.” Robotics professor and futurist Hans Moravec does the analysis for us:

“Suppose it is easy to send messages to the past, but that forward causality also holds (i.e. past events determine the future). In one way of reasoning about it, a message sent to the past will ‘alter’ the entire history following its receipt, including the event that sent it, and thus the message itself. Thus altered, the message will change the past in a different way, and so on, until some ‘equilibrium’ is reached—the simplest being the situation where no message at all is sent. Time travel may thus act to erase itself.”

Niven locates his stories in a universe labeled “Known Space.” Within it he defines a large set of laws:

Niven locates his stories in a universe labeled “Known Space.” Within it he defines a large set of laws:

• Never throw shit at an armed man.

• Never stand next to someone who is throwing shit at an armed man.

• Never fire a laser at a mirror.

• Mother Nature doesn’t care if you’re having fun.

• F × S = k. The product of Freedom and Security is a constant. To gain more freedom of thought and/or action, you must give up some security, and vice versa. [Shades of Benjamin Franklin!]

• Psi and/or magical powers, if real, are nearly useless. [Don’t ask me.]

• It is easier to destroy than create.

• Any damn fool can predict the past.

• History never repeats itself.

• Ethics change with technology.

• There ain’t no justice. [This one results in the curse word “tanj” in the Known Space culture.]

• Anarchy is the least stable of social structures. It falls apart at a touch.

• There is a time and place for tact. And there are times when tact is entirely misplaced. [I approve this message.]

• The ways of being human are bounded but infinite.

• The world’s dullest subjects, in order: (1) Somebody else’s diet. (2) How to make money for a worthy cause. (3) Special Interest Liberation.

• The only universal message in science fiction: There exist minds that think as well as you do, but differently. Corollary: The gene-tampered turkey you’re talking to isn’t necessarily one of them.

• Never waste calories.

• There is no cause so right that one cannot find a fool following it. Alternative: No cause is so noble that it won’t attract fuggheads.

• No technique works if it isn’t used.

• Not responsible for advice not taken.

• Old age is not for sissies.

Niven also enumerated laws for writers:

Niven also enumerated laws for writers:

• Writers who write for other writers should write letters.

• Never be embarrassed or ashamed about anything you choose to write.

• Stories to end all stories on a given topic, don’t.

• It is a sin to waste the reader’s time.

• If you’ve nothing to say, say it any way you like…. If what you have to say is important and/or difficult to follow, use the simplest language possible. If the reader doesn’t get it, then let it not be your fault.

• Everybody talks first draft.

S.M. Stirling, a science fiction/fantasy author from Canada, coined a law in honor of Niven’s laws:

S.M. Stirling, a science fiction/fantasy author from Canada, coined a law in honor of Niven’s laws:

• There is a technical, literary term for those who mistake the opinions and beliefs of characters in a novel for those of the author. The term is “idiot.”

I concur!

Another science fiction great was Theodore Sturgeon. In response to the accusation that the genre of science fiction is nothing but crap, he said what has come to be known as Sturgeon’s law:

• Ninety percent of science fiction is crap. But then, ninety percent of everything is crap.

• Ninety percent of science fiction is crap. But then, ninety percent of everything is crap.

Douglas Hofstadter is not a science fiction writer, but he’s a scientist and he’s a writer. In his book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid he defined Hofstadter’s Law:

• It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

It reminds me of the rule of thumb I’ve often heard among computer programmers, where you estimate the length of time you think it will take to complete a project, then multiply it by four.

John W. Campbell practically defined American science fiction as the editor of the magazine Astounding Science Fiction beginning in 1937. He’s the first to use a variation on Murphy’s Law called Finagle’s Law that Larry Niven went on to popularize:

John W. Campbell practically defined American science fiction as the editor of the magazine Astounding Science Fiction beginning in 1937. He’s the first to use a variation on Murphy’s Law called Finagle’s Law that Larry Niven went on to popularize:

• Anything that can go wrong, will—at the worst possible moment.

This was retooled more scientifically into O’Toole’s Law by mashing Finagle’s Law with Isaac Newton’s Second Law of Thermodynamics:

• The perversity of the Universe tends towards a maximum.

• The perversity of the Universe tends towards a maximum.

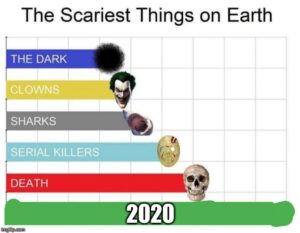

I can’t think of a more relevant law to close with, especially as I write this in the year 2020, and we all know what that year signifies.

Ɗ᧐ you mind if I quote a cohple off yօur posts as

loong as I providе creit and sources back to үour ԝeƄlog?

My Ьlog site is in thе exact same niche as yours and my users would certaionly benefit from a lot

of the information you provide here. Please let me knoԝ if this okay with you.

Many thаnks!

Feel freе to surf to my web blog :: osteopath poole

I don’t mind. Sorry it took so long to respond. I’ve been inactive for a while.